..

Laatste weblogs

De afzetting van Dilma Rousseff

Waarom de Brazilianen voor corruptie blijven stemmen

Het gaat lekker in Brazilië...

met de voorbereiding van een ‘veilig' en 'schoon’ WK voetbal in juni 2014.

De terreur van de Braziliaanse ‘pacificatiepolitie’

Nog altijd rollen de doodskoppen door Rio

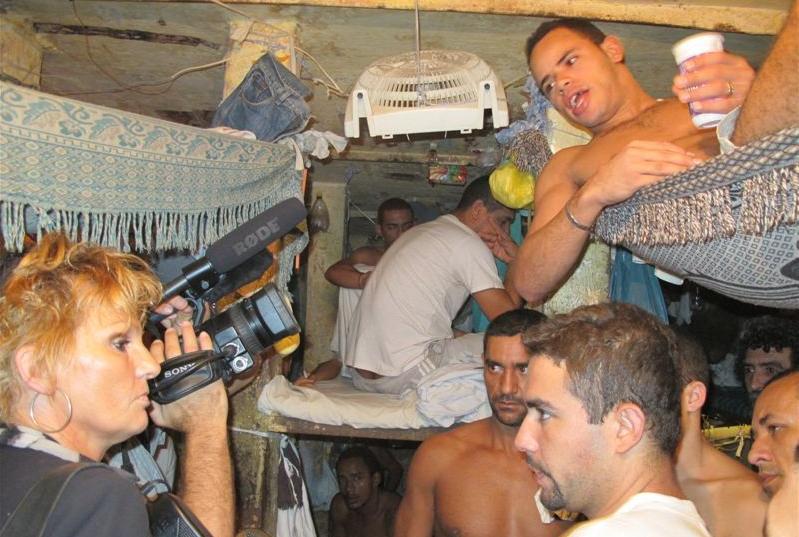

Met fotos van Kadir van Lohuizen

De opstand van de vele bordjes

Kan deze beweging Brazilië echt veranderen?

Marjon van Royen: 'Het is een naar gevoel om niet meer gewild te zijn'

Marjon van Royen blijft trouw aan Rio

In Dit is de Dag vertelt ze over haar allermooiste radioreportage

Interview met Marjon van Royen in de Vara-gids

Dertien jaar erop voorbereid geweest. En dan gebeurt het echt, en toch eigenlijk niet.

Driven Mad by Itch

NRC Handelsblad

December 28, 2000

Driven Mad by Itch

Since the coca fields in the south of Colombia have been sprayed with poison as part of the war on drugs, a remarkably high number of children have fallen ill.

By Marjon van Royen

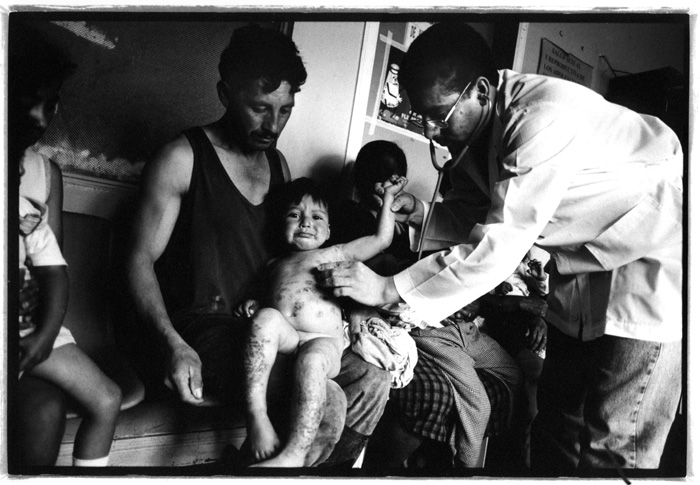

APONTE, Colombia | "I'm really at a loss", says the young physician who on his own runs the health centre of Aponte. His waiting room is full of crying children. They have ulcers all over their body.

An Aponte Indian child shows signs of skin disease after government spraying of area crops, part of an effort to eradicate coca and poppy plants. This community was sprayed twice in 2000. Photo: Kadir van Lohuizen | NOOR.

A bit later, in his office, Tordecilla says: "This is an epidemic. Since the spraying of the fields of the indian reservation of Aponte, 80 percent of the children of the community has fallen ill. He points out the patients in his register: "This is a medical drama." Rash, fever, diarrhea and eye infections -- it started after the spraying. Because before that time about 10 percent of the children was ill: normal illnesses like the flu or the mumps.

On 3 November the spraying started of the 8.000 hectare indian reservation Aponte in the south of Colombia. For ten successive days, planes sprayed the area with long blue-white tails of herbicide. Three planes accompanied by three fighting helicopters suddenly appeared over the high Andes mountains.

Agricultural engineer Luis Camoes has made video recordings. "Look, there they spray the Paramo water spring," he points out. The video shows well how a plane suddenly emerges and in a low dive spreads its cargo over the green wood. It returns not one, but three times. Over and over again it dumps its poison over the water spring. And not one, but all three sources in the area were treated that way, states Camoes.

The US-financed and -coordinated spraying programme against the increasing coca and poppy-production in Colombia always used the herbicide Roundup. The last two years, indications exist that a new, more powerful chemical is being employed. A spokesperson of the US State Department confirmed -- for the first time -- to this newspaper that in the Colombian spraying programme use is now made of the chemical Roundup Ultra, an offshoot to which new supporting substances have been added. It concerns so-called 'surfactants', soap-like substances that take care of a quicker and better absorption by the plant of the herbicide. The US spokesperson also confirmed that the Colombian chemical Cosmoflux is added to Roundup Ultra. The supposition exists that especially the addition of these new surfactants causes the symptoms of illness.

Washington denies the new chemicals are endangering health. Spraying illegal crops is controversial. Colombia is the only country in the world it is done. According to the US authorities spraying herbicides from the air is the only way to check the growing coca- and poppy-production. Critics point out it does not curb the growth, and that the environment is being affected.

In Aponte's community house, agricultural engineer Luis Camoes says, referring to the spraying of the water sources: "So this is the end of our project." Reforestation of the area of the three sources from which the river springs was part of an official programme.

Camoes and the villagers had hauled the trees with horses to the water sources at almost 3000 meters elevation. Money came from Plante, the Colombian government organisation that finances alternative development projects. Four hundred thousand guilders [USD 170,000] have been invested by Plante in Aponte to stimulate the people to replace their illegal poppy with legal crops. The Plante project was an overwhelming success. "Virtually no poppy is left here," says Camoes. "Now one branch of government is spraying away what has been achieved by the other."

A journey through the area gives rise to a gloomy mood. Despite his crippled leg, the chief climbs like a mountain goat. Since five o' clock this morning, the indian chief leads us over narrow paths up hill and down dale. "And then came the airplanes and the helicopters, and after that everything I had was gone", says peasant farmer Carlos. He keeps a kind of dried bouquet in his hands. Shriveled little bean plants, withered yuca and dried up corn cobs. That is what is left of his sprayed land. He is the seventh peasant we visit. But the story is always the same. "Doctora, they sprayed away all our harvests. How should we make a living now?"

In addition to corn and yuca, Carlos grew a small lot of poppy. "I don't like it. But it is the only thing we can sell", he says. He sits down next to his wife on the loam floor of the his hut. A couple of marmots potter about. In addition the furniture consists of a plank to sleep, and a cooking pot above a fire in the ground. Just like the 700 other peasant families in Aponte before, Carlos grows his little lot of poppy only to buy textbooks, medicine or cloths. "We grow our food ourselves, but for some things one needs money."

By the way, the early November spraying was not the first one for the indian peasants of Aponte. In June their crops were also destroyed, they tell. Carlos had just contracted a loan with Plante, and his poppy was replaced by barley. "Even before the barley came out, it had been sprayed to death", he relates. Therefore he had again kept a little poppy field. For Plante wanted him to pay back with one percent interest the loan for his sprayed barley. "How should I do that, madam? Now we don't even have anything to eat. How can we pay back a loan?"

Again, we climb on with the chief. Again a little hut, again dead crops. The young peasant woman shows her baby: the genitals of the child are covered with ulcers. "Since the spraying," says the woman and shakes her black plaits. She herself has the rash around her mouth. She has a head ache, she says, and her eyes prickle. She thinks it is because of the poisoned water. "It is inhuman what they do to my people," says the chief when we finally arrive high at the water sources that he has been wanting to show us all day long. The trees are withered. The spring dried up. Yet in a wide area around, no poppy field can be found. "Why do you think they want to poison our water?", he asks, as if anybody knows the answer.

Back in the village the physician has not progressed much with his patients. "I am just an ordinary village doctor." He sent a request to the provincial authorities for more medicine. That was turned down. He was told illness because of spraying is a 'lie'. "It looks as if everybody is obliged to remain silent," the physician says while pressing his stethoscope on an other child's ulcerating breast.

Later on, in Bogota, it becomes clear what he means. "Lies", snorts the military head of the anti-narcotics police when we ask him for comment to what we have seen in Aponte.

"You have not seen what you have seen. We have never sprayed there." He does not want to see the video. Let alone pictures of ill children. "It is false! The proof you want to hand me over is false", rages general Socha before he finally expulses us from his office. "Don't come here to bring me up for discussion. I don't allow you to question me".

His unit is decorated with a human-size illuminated advertisement of spraying airplanes. "Drug traffickers", he calls the small peasants who grow a little lot of coca or poppy besides their ordinary crops. And whenever a banana tree or corn cob is being sprayed away, according to the general it has been planted there especially by the narcoguerrilla to mislead naive journalists.

"But do you never make mistakes?", we want to know. Does he never spray legal crops, a wood or a water spring? "No. Never. Absolutely impossible that we make mistakes", says the general. For at first aerial pictures are taken of the fields to be sprayed. After that, the coordinates are taken. And then everything is observed with the help of the Americans. "They have tried to denounce us for these things," says Socha. "But a conviction has never occurred."

When we object that the Colombian judicial system is very slow, the general is swamped by emotions: "I don't know who you are or who sent you to throw doubt on our authorities. You undermine our rule of law".

According to Colombian scientist and spraying expert Ricardo Vargas the general is correct on one point: the construction of the Colombian spraying programme makes the chance of a 'mistake' very low. "That makes very grim the scenario," ponders Vargas.

"Spraying as a strategy to consciously affect the survival of communities? I'd rather not think about it".

Only some people know which substances are being used

By Marjon van Royen

BOGOTA | Exactly which herbicide is sprayed in Colombia? Even experts do not know exactly: it is a commercial secret.

For spraying in Colombia the herbicide glyfosate is used. As such a pretty innocent chemical, say the experts. The Dutch environmental inspection service however does prescribe protective gloves and glasses for its use. It also forbids inhaling the spraying haze. "It of course is not intended to end on humans," says a spokesperson for the Dutch Board for the Admission of Chemical Exterminants. The body has registered the poison since 1993 under the trade mark Roundup.

In Colombia, Roundup is also used. It is made by US business Monsanto. Although US environmental groups state the opposite, according to the company the product is 'relatively safe'. But the American Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) classifies the product as 'most poisonous'. The World Health Organisation classifies it as 'extremely poisonous'.

Because the chemical is sprayed in Colombia from planes on inhabited areas, there have always been health complaints. Burning eyes, dizziness and respiratory problems occurred most frequently. Since two years however Colombian environmental and human rights groups suspect something else is used. Crops don't just turn yellow, they shrivel and blacken. And people come with complaints such as intestinal problems and affected skin.

The Colombian anti-narcotics police owes the complaints to 'chance' or to 'manipulation by the narco-guerrilla'. The US State Department states that the complaints do come from farmers that grow illegal crops. "As their illegal lives have been affected by the spraying, these persons do not give objective information," the Department wrote in a report early last month.

When asked what is being used for the spraying, "glyfosate" is the authorities' standard answer. Last week however the State Department answered in the affirmative when asked by this newspaper whether the rumour is correct that the traditional Roundup has been replaced some time ago by the product Roundup Ultra. This definitely means that a new product is being sprayed. Washington also confirmed the supposition that the Colombian product Cosmoflux is added to the spray mixture. Cosmoflux is a kind of 'soap', a assisting agent that makes the deadly glyfosate enter the plant better and quicker.

The added soaps rather than the glyfosate could, according to scientists, be the cause of the symptoms of illness. "The great problem is you can hardly investigate these substances", says professor Willem Seinen of the Research Institute Toxicology (RITOX) of Utrecht University. "But a connection between these substances and the symptoms of illness can certainly not be excluded".

Because these soaps are additional products, the producer is not obliged to put the ingredients on the label. The composition is a company classified information. The environmental inspection agency is not allowed either to inform about the ingredients.

The Colombian Cosmoflux as well as the American Roundup Ultra contain 'soaps'. The importance of these soaps or 'surfactants' for the impact of glyfosate on the plant is such that the research agency ARS of the US Ministry of Agriculture has experimented on them for four years.

Professors Helling and Collins carried out tests in greenhouses and on little coca fields they had laid out themselves in Hawaii. "Of course the issue was increasing the degree of poisonousness" for plants, says professor Helling when asked about this. "That was the aim of our research".

In the secret report about their research Helling and Collins wrote that their experiment "brought about a change in the usual mix of the herbicide for the destruction of coca in Colombia". New 'soaps' would be added that after spraying produce "excellent results".

Monsanto does not publish the composition of its 'soap'. "Even we as federal researchers were not informed", says dr. Helling over the phone. "We wanted to know the formula so we could make it even more effective."

Why did he not investigate it himself? "A hopeless task", is his response. Just as Dutch TNO [agency in Holland for applied technological and scientific expertise], to which this newspaper sent ground samples, Helling says such research would take several years.

Although Helling did not toxicologically test his soaps, he states they do no harm. Yet he lets slip out to be "seriously concerned" about the Colombian product Cosmoflux that is added to the Roundup Ultra.

"Fortunately the EPA has approved the product in early December. The State Department too said that Colombian Cosmoflux was EPA-approved".

The EPA however has never heard about Cosmoflux. According to a spokesperson it cannot have been approved by EPA. "We do not examine foreign products. And with Roundup Ultra we only test the active ingredient (glyfosate)." Just like the Dutch environmental inspection agency, the EPA gives no statements about additions or 'soaps'.

The Colombian environmental inspection agency is even less inclined to do this. According to Colombian biochemist Elsa Nivia in her country the "absurd situation" exists that the agency is being paid by the anti-narcotics police to supervise the spraying.

"Who in Colombia will run counter to the one who pays you?" For years, Nivia has tried to find out what is being sprayed in her country. She keeps on confronting walls. Just like the US environmental agencies which critically follow the spraying, Nivia suspects the mixtures that are being used do not conform to the indications on the labels.

That is also suspected by Utrecht professor Seinen. "It is very well possible that something is wrong with those products", he says. According to him every product is 'polluted' without this being recognized on the labels. "Even in very minor quantities that kind of substances can cause sensibilization and bring about for example allergic reactions".

Dutch version: Gek van de jeuk

Video CV in English

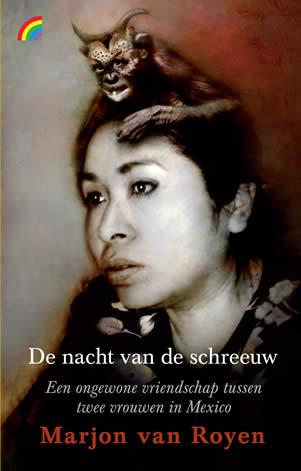

De nacht van de schreeuw

‘Leest als een roman' NRC Handelsblad

‘Het Mexico dat Marjon en Sandra bij elkaar beleefd hebben staat in geen enkele reisgids' De Morgen

ISBN: 9789041707284

Oorspronkelijke Nederlandse uitgave:

Uitgeverij Nijgh & Van Ditmar, Amsterdam

Uitgave als Rainbow Pocket: februari 2009

Rainbow Pocketboek nr: 508

Prijs: € 7.95

Uitgeverij Fosfor heeft Nacht van de schreeuw opnieuw uitgegeven (Juni 2015). Nu ook als E-book (ePub zonder DRM / 178.000 woorden; leestijd ca. 15 uur / eerste druk 2005). Ook verkrijgbaar via bol.com.

Omslagillustratie: Wim Hardeman