..

Laatste weblogs

De afzetting van Dilma Rousseff

Waarom de Brazilianen voor corruptie blijven stemmen

Het gaat lekker in Brazilië...

met de voorbereiding van een ‘veilig' en 'schoon’ WK voetbal in juni 2014.

De terreur van de Braziliaanse ‘pacificatiepolitie’

Nog altijd rollen de doodskoppen door Rio

Met fotos van Kadir van Lohuizen

De opstand van de vele bordjes

Kan deze beweging Brazilië echt veranderen?

Marjon van Royen: 'Het is een naar gevoel om niet meer gewild te zijn'

Marjon van Royen blijft trouw aan Rio

In Dit is de Dag vertelt ze over haar allermooiste radioreportage

Interview met Marjon van Royen in de Vara-gids

Dertien jaar erop voorbereid geweest. En dan gebeurt het echt, en toch eigenlijk niet.

Earthquake-report from a backpack correspondent

Tuesday, March 9, 2010

Saturday morning half past three earthquake Chile. Less than three hours later Holland gives the green light: ‘Marjon, you go.' I stuff my computer and some equipment in a backpack. Across the street cameraman Joe Carter does the same. And there we go.

Saturday morning half past three earthquake Chile. Less than three hours later Holland gives the green light: ‘Marjon, you go.' I stuff my computer and some equipment in a backpack. Across the street cameraman Joe Carter does the same. And there we go.

In the plane to Argentina (airports Chile closed) we meet our colleague from the German sister network ZDF. ‘Hey Karsten, shall we share a car rental?' He returns a blank stare: ‘Hire a car?' Slowly he starts laughing: ‘Mensch, we rented a private airplane. And we have a team of eight.'

Mini generator

Fourteen hours later Joe and I fish our sports bags off the baggage belt. Now we see what Karsten meant: The ZDF production crew load one box after another from the belt. Aluminium boxes full of batteries, satellite telephones, and modern mobile internet-equipment. They even have a mini generator for power, Karsten explains.

Taxi driver

‘Auf wiedersehn than.' While Karsten and his men are building towers of boxes on their luggage carts, Joe and I are already looking for a car. With our feather light luggage it doesn't take long before we meet a taxi driver, crazy enough to take us to Chile. His name is Vicente: ‘Like Vincente van Gogh, but with two ears', he laughs companionably. He is Chilean. Imprisoned and tortured during the dictatorship of Pinochet. He later escaped over the Andes to marry a local Argentine beauty. ‘I am anxious to see what the quake has done to my country', says Vicente.

‘Auf wiedersehn than.' While Karsten and his men are building towers of boxes on their luggage carts, Joe and I are already looking for a car. With our feather light luggage it doesn't take long before we meet a taxi driver, crazy enough to take us to Chile. His name is Vicente: ‘Like Vincente van Gogh, but with two ears', he laughs companionably. He is Chilean. Imprisoned and tortured during the dictatorship of Pinochet. He later escaped over the Andes to marry a local Argentine beauty. ‘I am anxious to see what the quake has done to my country', says Vicente.

Thus the three of us become a crew.

Border

Vicente speeds his Ford Focus over the Argentine planes. At a gas station I withdraw as much money I can get, and we fill up the car. Extra jerry cans for later in Chile, bottled water and junk food.

Vicente speeds his Ford Focus over the Argentine planes. At a gas station I withdraw as much money I can get, and we fill up the car. Extra jerry cans for later in Chile, bottled water and junk food.

After seven hours we crawl up the Andes. Tortuous roads. Now and then scattered with rocks loosened from the mountains during the earthquake.

We have to hurry up, because the border closes at six PM, Vicente informs us. Made it! Six sharp. Some freezing custom officers among the lama's and their herdsmen. They politely take our food, because the import of comestibles is forbidden in Chile.

Hobbling

Vicente is beaming. ‘Do you smell the difference? The Chilean air', he shouts hanging out of his rolled down window. He turns right on a dirt road. Waggling through the deserted moon landscape of the Andes. I don't yet smell Chile, only an oncoming rainstorm. ‘Vicente, are you sure this is the right way?' Except for falcons, there is nobody to ask.

Ghost town

At midnight we finally drive into the first Chilean town. Talca has become a ghost town. In the light of the moon the silhouette of ruins take shape. Stumbling over fallen telephone poles, electric cables. Here and there a fire. People in front of their crumbled houses.

At midnight we finally drive into the first Chilean town. Talca has become a ghost town. In the light of the moon the silhouette of ruins take shape. Stumbling over fallen telephone poles, electric cables. Here and there a fire. People in front of their crumbled houses.

We film. I also record for radio. But will our work be futile? How do we get our reports to Holland, without electricity?

Fortunately my Brazilian cell phone works. It still has battery power. Joe's phone is dead, and Vicente's doesn't get any signal. Quickly I do my radio talk for the morning program. Then to sleep. In the remains of a hotel. Only the moon as a light, no food. And after a few hours up again to film how the town reveals itself at dawn.

Radio station

Destruction. Roaming people. Entire families sleeping on the streets. And yet, the disaster doesn't seem as horrendous as Haiti. Or have I become desensitized? No time to think. We have to edit. Electricity is what we need. Is there somewhere a place with a generator maybe?

Destruction. Roaming people. Entire families sleeping on the streets. And yet, the disaster doesn't seem as horrendous as Haiti. Or have I become desensitized? No time to think. We have to edit. Electricity is what we need. Is there somewhere a place with a generator maybe?

'Try the radio station', says an old man on the pavement, surrounded by the few belongings he salvaged from the ruins of his house. ‘They must have one. Yesterday they broadcasted the whole day.'

Aftershock

It's a sensation similar to when you get drunk, only without drinking. Screaming, everybody ran out of the radio station at the aftershock. For Joe and I finally the occasion to actually hear what we are editing. One square meter on the floor, between the toilets and the directors room we were granted a little space to work. Around us chaos. Shouting people. Authorities who upload their phones at the only available electricity point in town. Outside desperate people trying to force the doors of the station. But the aftershock gives us a moment of relief.

Quickly we finish the piece, because the generator just ran out of gas. ‘Here's an address where they have internet', the director whispers as he hands us a note.

Eureka

‘Vicente, Vicente, your driving skills will make the difference between a report, or no report from Chile.' In Holland now it is quarter past seven. Only 45 minutes before the Eight o' clock news. Hopelessly lost we drive through the destroyed town. There, there it is, an internet café!

‘Vicente, Vicente, your driving skills will make the difference between a report, or no report from Chile.' In Holland now it is quarter past seven. Only 45 minutes before the Eight o' clock news. Hopelessly lost we drive through the destroyed town. There, there it is, an internet café!

Alas, closed. ‘If I had power, I would let you use my internet for free', a sympathetic neighbour says.

'Power', screams Vicente. ‘Eureka, that's it! Get in the car quickly you rabbits. I will save your asses!'

With skreaking tires he speeds off. Vicente tells how -looking for gasoline- he heard that in a far part of the city electricity has returned. ‘And thus maybe internet.'

Bite my knuckles

The clock ticks. And my heart sinks. In Holland it is now half past seven, quarter to eight... We're not going to make it. ‘Vicente, why are you stopping? Where are you going?' On his short legs we see him running across the street. A minute later he is back. ‘Hurry, this is the ticket office of a bus company', he gasps. ‘They are closed. But they have electricity, and internet.'

The clock ticks. And my heart sinks. In Holland it is now half past seven, quarter to eight... We're not going to make it. ‘Vicente, why are you stopping? Where are you going?' On his short legs we see him running across the street. A minute later he is back. ‘Hurry, this is the ticket office of a bus company', he gasps. ‘They are closed. But they have electricity, and internet.'

While I still talk to the bewildered secretary, Joe has already jumped over the counter, and rips out their DSL cable to plug it into his computer.

‘Shit Marjon, the server of the Eight o' clock news is kicking me off!'

'Send it to the Late Night show. They can pull it from there!'

Without breathing, looking for a miracle, six pairs of eyes see how the site slurp up Joe's bites. Ping. ‘Transmission successful'. Seven minutes to eight. We're saved!

‘Ladies, this is the quickest internet I have ever met in Latin America', Joe compliments the saleswomen with a kiss on the cheek. (See tv-report here)

Sweet firemen's family

And so we move on. To the totally destroyed coast town of Constitución. We film the search for survivors. The dead being brought to the Sports stadium for identification. The young woman who lost her daughter and five other family members. We have to tell her story. But how?

And so we move on. To the totally destroyed coast town of Constitución. We film the search for survivors. The dead being brought to the Sports stadium for identification. The young woman who lost her daughter and five other family members. We have to tell her story. But how?

Again it is Vicente who comes on the rescue. This time with a friendly fire station. A family of volunteer firemen and women welcome us with internet, electric power, water and apples. Our money has run out. Our remaining dollars are spent on gas. Brazilian reais are of no use, without banks or exchange offices. And Vicente just spent his last Chilean pesos on us. (See tv-report here)

Gasoline and apples

'Go to Concepción', my bureau chief orders over the dying phone. ‘It's near. It's a big town. And they must have everything.' He clearly didn't look at Google earth. Concepción is hundreds of kilometres. And most of the road is destroyed. But a boss is a boss.

At the petrol stations kilometric lines of cars. Gasoline is limited to a few litres per car. Even if we had money, it would take us a day for our turn to fill up.

So we suck some petrol out of a rolled over truck with other looters. The farmer behind it, offers fresh apples to appease our hunger and thirst.

State of siege

'You permits please'. Guns drawn at the military roadblock that night on the highway. In Concepción the government has ordered a state of siege. Because of plundering, nobody is allowed in or out of town. But we have paperwork. Joe adulterated the military laissez passer of a colleague. A clearance the colleague got in his name at supreme headquarters in Santiago. With our names now and Vicentes' number-plate, seven military checkpoints later, we drive into yet another dark ghost town.

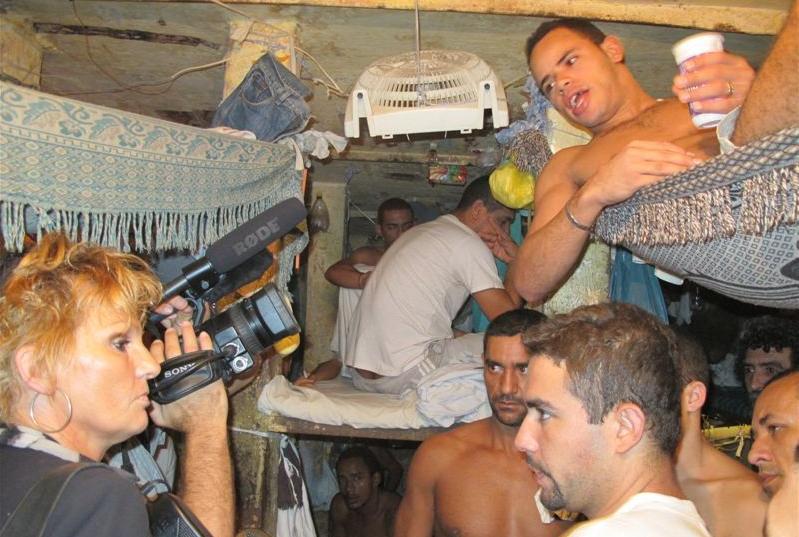

Backpack journalists

We want to film the looting. But we can't see our hands in front of our eyes. 'There', cries Vicente. 'A light.' Ahead in the dark looms a fairytale-like house, with a saddleback roof. When we come closer we see cosy shaded lamps and people drinking wine behind the curtains. An surreal vision among the destruction.

We want to film the looting. But we can't see our hands in front of our eyes. 'There', cries Vicente. 'A light.' Ahead in the dark looms a fairytale-like house, with a saddleback roof. When we come closer we see cosy shaded lamps and people drinking wine behind the curtains. An surreal vision among the destruction.

'Marjon', exclaims a dark haired man as we enter the crowded sitting room. ‘How did you get here?'

Puzzled he comes out of his armchair. Only now I recognize him. It's Jeffrey, the correspondent of American network ABC. Three weeks ago he was still drinking beer on my balcony in Rio.

What is he doing here I want to know. How did he get electricity?

'We rented the place for the crew', he dismisses. 'We flew in some stuff. But tell me, where is your crew?'

Proudly I point at Joe and Vicente.

'No!' Laughing he stares at me. Than he starts clapping his hands. 'People, guys, silence for a minute! Can you get the others out of their rooms? Because I want you all to see this: Those three. See them?', he asks pointing at us. 'Here stands the team of Dutch Public Television.' The room echoes with laughter as he fills everyone's glasses up. 'Backpack journalists', he chuckles. 'Real backpack journalists! Can you believe it?'

Expensive Equipment

When at 4.30 AM we crawl out of bed with our apple stomachs, Jeffrey and his 20 men are still asleep. We want to film the looting and the civilian militias in the destroyed port near Concepcion. 'No way am I going to risk myself with our expensive equipment out there', Jeffrey had said the night before.

When at 4.30 AM we crawl out of bed with our apple stomachs, Jeffrey and his 20 men are still asleep. We want to film the looting and the civilian militias in the destroyed port near Concepcion. 'No way am I going to risk myself with our expensive equipment out there', Jeffrey had said the night before.

By the time the sun is up, we have filmed everything, and have befriended the looters. In the refugee camp on the hill, we have exchanged cell phone numbers with the homeless. And the militias have invited us for coffee and showed us their weapons. (See tv-report here)

As far as I can check, none of the big networks have yet to arrive.

So, a toast to backpack journalism!

Video CV in English

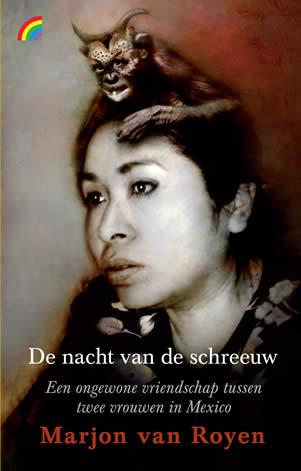

De nacht van de schreeuw

‘Leest als een roman' NRC Handelsblad

‘Het Mexico dat Marjon en Sandra bij elkaar beleefd hebben staat in geen enkele reisgids' De Morgen

ISBN: 9789041707284

Oorspronkelijke Nederlandse uitgave:

Uitgeverij Nijgh & Van Ditmar, Amsterdam

Uitgave als Rainbow Pocket: februari 2009

Rainbow Pocketboek nr: 508

Prijs: € 7.95

Uitgeverij Fosfor heeft Nacht van de schreeuw opnieuw uitgegeven (Juni 2015). Nu ook als E-book (ePub zonder DRM / 178.000 woorden; leestijd ca. 15 uur / eerste druk 2005). Ook verkrijgbaar via bol.com.

Omslagillustratie: Wim Hardeman